Our Great Leaders

Our great leader(s)

Book reviews by Enchanted England

November 2020

Dear Reader, here we are marooned in second lockdown that once again forced a retreat into the library. From where, at least, I can report some good news. The battle of the books has largely been won in that they have been sifted, selected and re-shelved. Fifteen boxes of boxes were shipped out to the Oxfam bookshop. The library tribe although restive is a least catalogued or so I thought as I slotted the last stray paperback into place.

A book by chance caught my eye. Vita Sackville-West and Sissinghurst gardens. Why not review that suggested my husband. But I was in no mood for roses and collapsed onto a sofa and flicked on the TV instead.

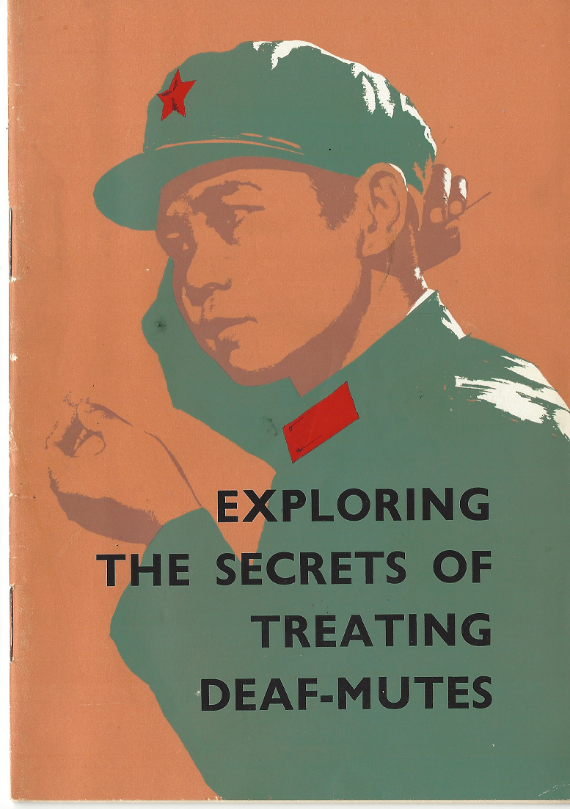

Big mistake. The library tribe outraged by this rejection, simmered and then and I am not exaggerating to say launched the following book onto the floor. No-one in the house has seen this slim volume and denies all knowledge of how it came to be here. It is simply one of the most chilling books I have ever read. Printed in immaculate English by the Foreign Languages Press – PEKING 1972. It introduces a hero of the Cultural Revolution - Dr Chao Pu-yu.

On close inspection, he turns out to be a barely educated medical assistant who taught himself acupuncture. His dream was to ‘cure’ children with speech and hearing impairment in order that they could sing the praises of Chairman Mao.

To this end, he inserted acupuncture needles into the back of the skull to a dangerously unprecedented depth of 8 centimetres (2.5 cun). He claimed this stimulated a nerve that would allow speech and hearing to return. He took this news to his bourgeois doctor colleagues. Unable to argue, I imagine, they were forced to repeat this experiment on themselves under the watchful eyes of the Chinese Red army who pronounced it a success. Despite the pain and side effects of burning throats and numb limbs the treatment was rolled out to China’s unfortunate children. The little men, said Dr Chao Pu-yu, had defeated the big men. Thanks to our great leader Chairman Mao, today deaf-mutes, regain their speaking power.

To escape this ghastly tale of the worst excesses of a political personality cult, I turned for light relief to the Stuarts, of petticoats and kings.

Arbella – England’s Lost Queen by Sarah Gristwood ISBN 0-553-81521-0 and

A Gambling Man – Charles 11 and the Restoration by Jenny Uglow. ISBN 978-0-571-217342-2.

Both promised to be a lively and entertaining romp. Sarah Gristwood wisely started her book at the high point in Lady Arbella Stuart’s dramatic life. We find her on the run having escaped from the Tower of London, fleeing the wrath of King James 1 to elope with her husband and start a new life in the Netherlands. Gristwood begins here and shows what led Arbella to this point.

Niece to Mary Queen of Scots and second cousin to Elizabeth 1, she had a claim to the English throne that was dangerously overstated by her family. From the start her title of lost queen seems over-egged by Gristwood; one can imagine an exasperated Elizabeth shouting if you think you can be queen our Bella, you can think on. Certainly, a misogynistic James 1 had no truck with such nonsense. Yet her family, desperate for power, played a dangerous political game and lost. Their pawn, Arbella, therefore, was closely monitored and confined. She was surrounded by people who reported her actions to the court and was deprived of privacy. As a child, she was close to her aunt Mary and would have heard first-hand the dismal news of her botched execution. Arbella became paranoid, wrote frantic and fantastical letters, developed eating disorders and suffered mysterious ailments. Her ending was a lonely and painful one.

Uglow on the other hand starts with the story of the Winter King – Charles the First being replaced by the Summer King – Charles the Second returning to his lost Kingdom in late May sunshine. With a hey nonny nonny no, let the good times commence in Merry Olde Englande. Nell Gwynn, theatres, naughty Pepys, oranges, dancing, petticoats and lace, etc.

Shadows fall across this bright day. Uglow introduces Charles 11 as a man who, like Arbella, had no certain prospect of the throne. During his years in exile, he was watched and manipulated, poor and sneered at, in many ways this mirrors Arbella’s strange childhood. Once restored to power Charles’ manner of government grew ever more secretive and malign. The court was a hot house where women were used as pawns by their families to get money and power via the King’s bed – of revelling, drinking and whoring as one pamphleteer memorably put it. The king himself raged at women who disagreed with him; not so much a ladies man but a lady killer, even if he did not go so far as to cut their heads off. He set the tone where his palaces became a place where females were routinely preyed on. In the wider sphere, religious and political beliefs were restricted, spies were everywhere and innocent men routinely executed. No wonder the populace threw out James 11- who wanted more of the same and worse. This merry monarch was largely a manufactured mythical creature.

Three revolutions have taken place in my lockdown reading, the Chinese, the overthrow of Charles First and the Glorious Revolution starring James 11. When I was younger, I wondered how people endured. How did the Howard family oversee a show trial and execution of Anne Boleyn and then sacrifice Catherine Howard – her cousin – on the same altar. Education teaches us to read history as political ‘isms’, socialism, communism, capitalism, Protestantism, Catholicism, triumphalism and all their shouty proponents. How do we live under these systems that promise to make our lives better and fail us so greatly?

Tucked into Arbella’s story Gristwood gives a tiny compelling postscript to a truly lost queen; Lady Jane Grey, who was also related to Arbella. Catherine, sister to the nine-day queen, lived, wrote her Uncle, ‘in a miserable and most woeful state. Of how I never saw her but found her weeping or saw by her face she had wept.’ The failed political systems and history rarely record the grief they cause to those they fail.

We cannot know what happened to the children treated by ‘Dr’ Chao Pu-yu or the suffering of doctors who asked for scientific evidence in the face his magical thinking. But, when faced with leaders who deny facts, who ask us to buy into their spectacular media crafted personalities, or demands that we report our neighbours to an unelected police force that restrict family ties and our ability to pray; we might remember that democracy does not end in an ism and we can think on Arbella, we can think on.